Option Selling ETFs Are... Actually Pretty Good.

We can't just sit back and collect premiums without a catch, right?

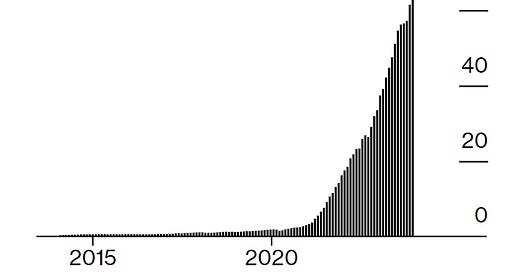

Ever since the introduction of 0-DTE options, the business of selling options has taken off and not looked back:

And it’s for really good reason — we’ll be doing a thorough update of our own option selling operation soon, but just to loop you in; we’re 2 months in and still cleaning house:

But today, this isn’t about us.

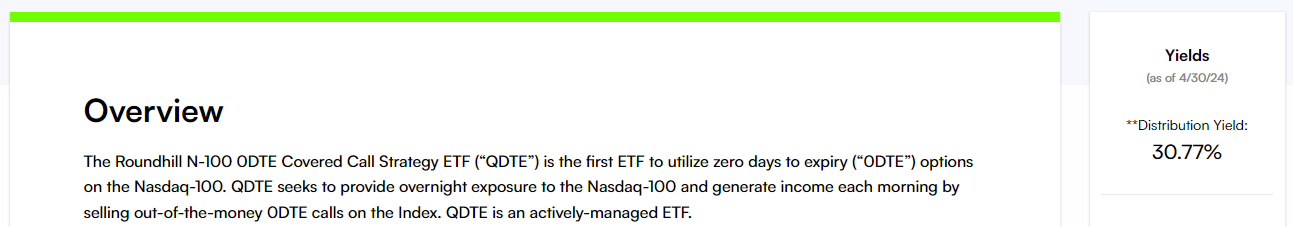

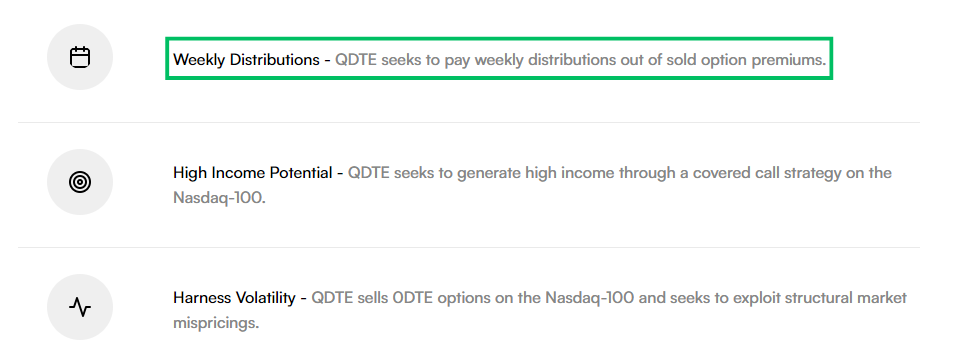

Today, we want to take a deep dive into a new breed of ETFs that primarily sell short-dated options to boast obscenely high dividend rates:

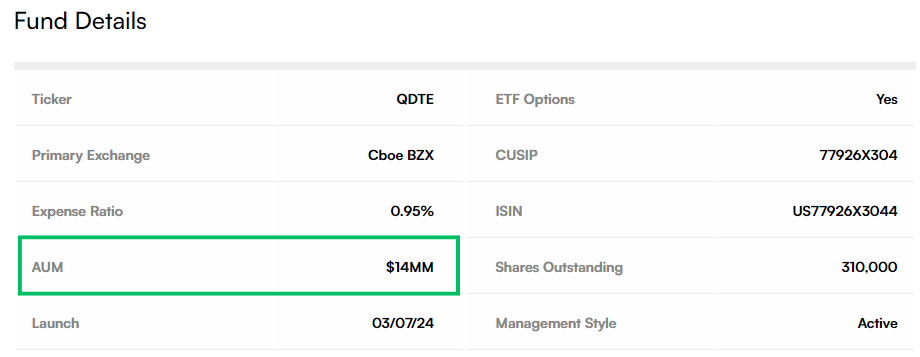

These funds essentially aim to sell options at scale and distribute most of the income to shareholders. For this generosity, most of these funds charge roughly a 1% expense ratio. Despite the attractive offer, these funds are relatively niche, with assets under management (AUM) often being less than $15 million (for reference, SPY’s AUM is ~$500 billion):

Looking at one such fund, YieldMax’s NVDA Option Income Strategy ETF, we can get a glimpse into how things have been going so far:

Comparing the prior month’s dividend to the most recent share price implies a 10% dividend payment paired with capital appreciation. Normally, when a stock or fund pays a dividend, it’s around 1-2% a year, so making 10x that in 1/12th the time raises some eyebrows and gets our attention.

After all, if it’s that easy, can’t we just max out our margin, go all-in, collect a few thousand every month and sail off into the sunset?

So, today we’ll be diving deep to find out exactly how these funds work and to ultimately answer the question of “what’s the catch?”.

Disclaimer: We have no affiliation with any of the funds mentioned, nor do we hold any positions related to them.

How Do These Things Even Work?

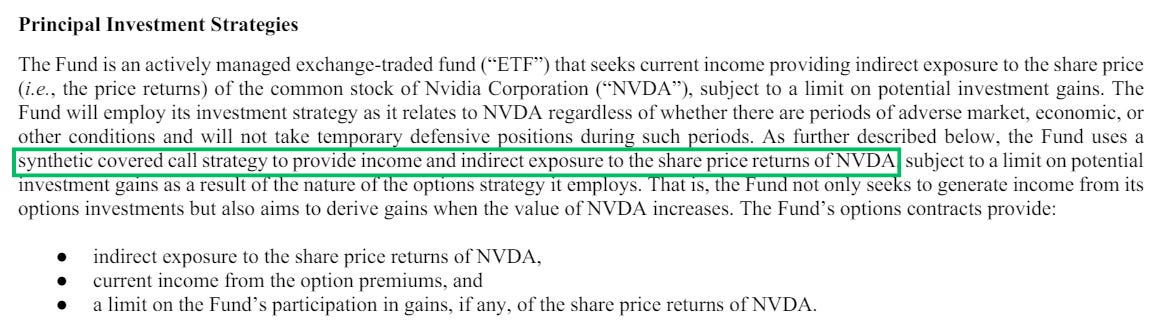

To start, let’s take a quick look at the prospectus of YieldMax’s NVDA Option Income Strategy ETF (NYSEARCA: NVDY):

Okay, so by using options to replicate a long position in the underlying, the fund then sells calls on that position and pays out the income. The language used may seem a bit esoteric, so let’s break it down.

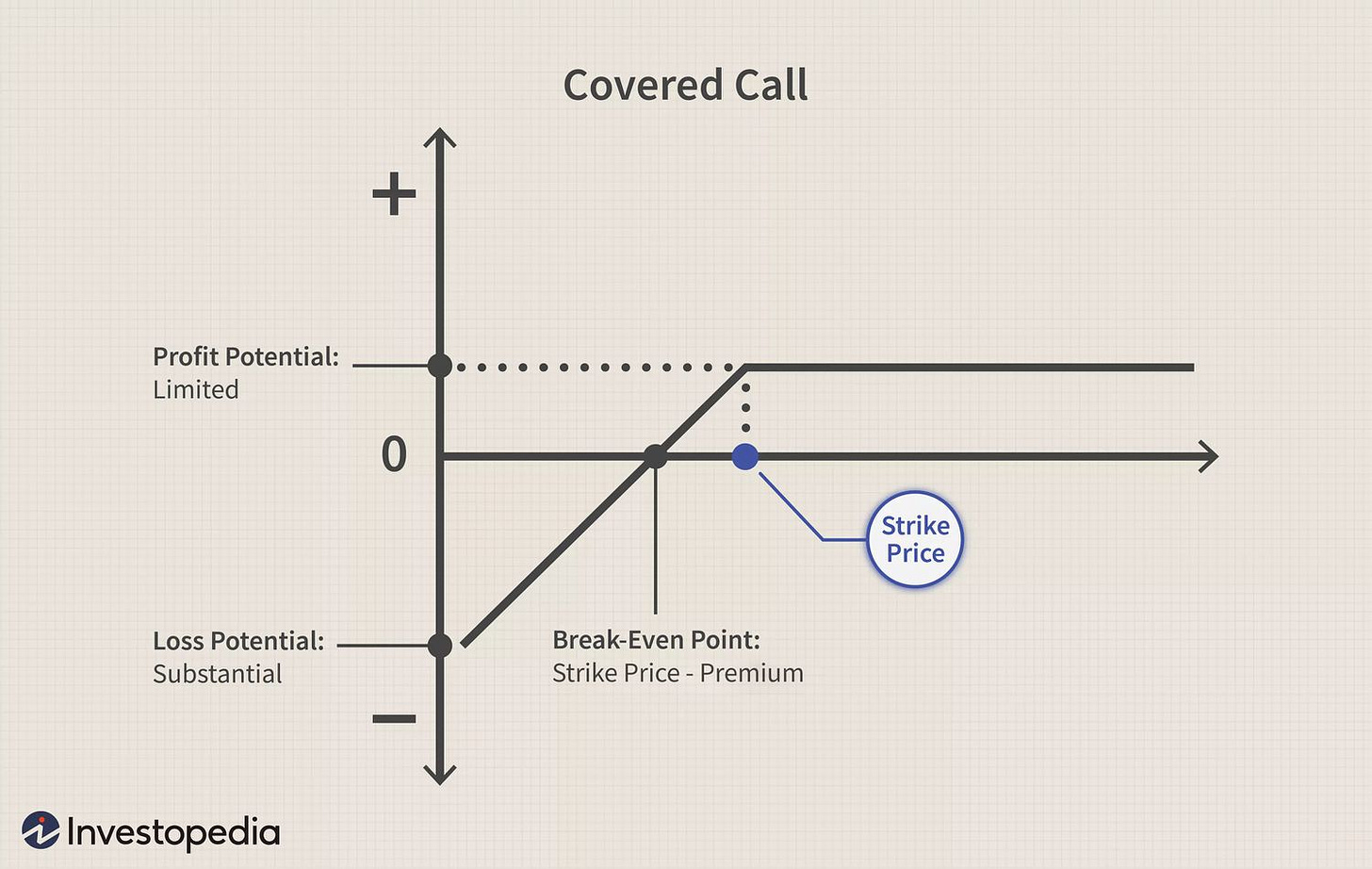

To understand any of this, we first have to understand the dynamics of a covered call:

Assume you have 100 shares of Stock A purchased for $100.

You sell a $105 call and receive $10 for doing so.

If the price of stock A rallies, your call buyer executes and your shares get called away at $105, resulting in a profit of $5 (105-100).

If the stock price doesn’t rally or even falls, you collect the $10 for the option.

Simple enough — your short call provides limited upside and in exchange, you get income for continuing to sell those calls.

However, with these funds, there’s a slight twist.

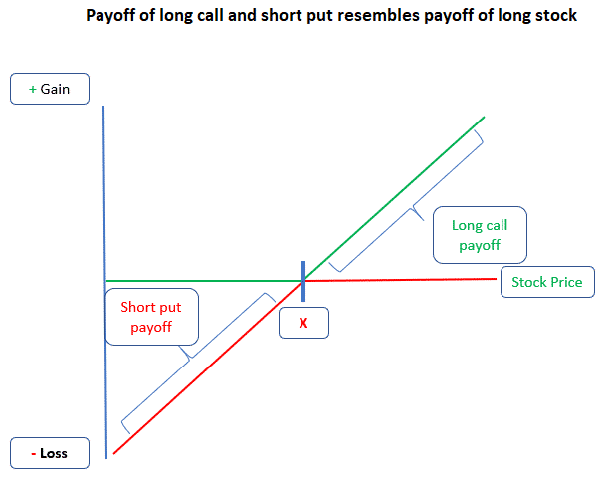

Instead of buying the shares and holding them, the fund instead replicates long exposure with a synthetic future. This essentially involves buying a call and simultaneously selling a put at the same strike:

So, with this cheaper, synthetic long position, the fund then sells out-of-the-money calls. The fund collateralizes the position with treasuries, which also generate income.

A cheaper structure is also seen in Roundhill’s 0-DTE Covered Call ETFs, where that fund uses a deep-ITM long call to act as the synthetic position. Fun (or frightening) fact, that ETF uses FLEX options (negotiated strike prices) and their long call strike is 420.69. On the other hand, some funds actually hold the shares of the underlying (e.g., Global X Nasdaq 100 Covered Call ETF)

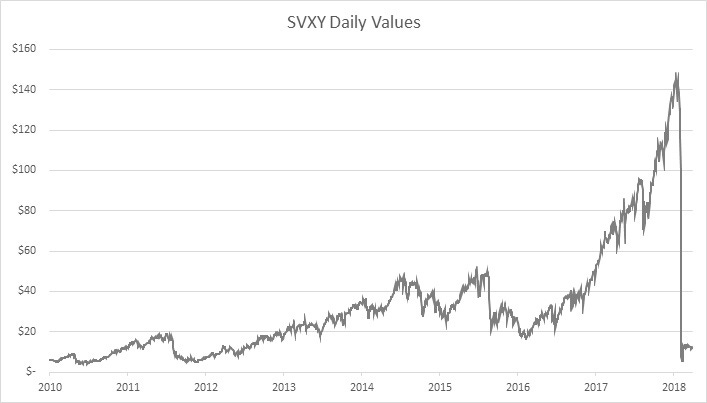

Right off the bat, there doesn’t seem to be any glaring red flags. Many fears about short option funds come from volmageddon style scenarios, where in the event of a sufficiently large move, the fund gets wiped out:

However, with covered call strategies, the risk factor mainly comes from if the underlying price falls in such a way that the income doesn’t outpace the drawdown.

To better understand the nuances of this risk, let’s check out a real-world example: